The other day, my daughter called and asked me about a recipe. We chatted about its origin, and recalled a funny story that went with it. Our lively conversation had stemmed from a simple question. Recently, I’ve been paying close attention to questions and their resulting conversations.

“Do you have an idea for your digital story?”

“How was your Fourth of July?”

“What’s the best way to get ketchup and red wine out of a table cloth? ”

“Who can help me with Weebly?”

“Could you look at this piece to tell me if the transitions work, and if the ending is strong enough?”

Each of these is a question I heard asked by someone during their time at the CRWP Summer Institute. Each of these led to discussions between two or more people. Sometimes the discussions were short, other times they were long, and a time or two the discussions were later revisited. Although it might appear that the conversations were casual, they were still interactions in which two or more people needed to communicate with others and needed to know what others knew in order to help their own learning or thinking.

The idea of conversation intrigues me. The more I listen to conversations, the more I think about how we use conversations to learn and grow, and the more determined I am to make them a habit of priority in my classroom and in the classrooms of others. Many years ago, before the Penny Kittle and Donalyn Miller push for creating active readers, I knew that to be a better writer I would need to look at how other things were written. I spent time mulling that over, thinking about how I could use it in my classroom. I decided that my students needed to understand that in order to write something others want to read, we need to read something that others have written. As we do, we think about the moves the author makes. I began teaching that to my students, telling them they needed to ‘read like a writer.’ I modeled, I applauded their efforts, and I inwardly rejoiced when they began to naturally use language to talk about writer’s craft. Now, I have a new habit for my students to focus on doing. It is simply, yet complicatedly, talk.

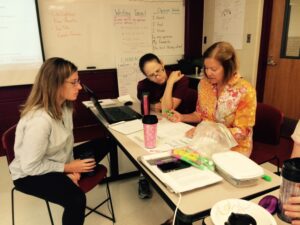

Our work in writing groups is one example of how we use talk. A writer tells her group what she’d like help with, then reads her writing as the group listens and follows along on their copies. They talk about the writing while the writer listens and takes notes. When finished, the writer is invited back into the conversation, commenting about what she is thinking as a result of the talk. Sometimes, the writer rearranges a phrase or two. Often times, the writer has had an aha! moment, and excitedly talks about revisions the work will undergo. Always, there is insight. Comments like “I never thought of that!” and “I like the suggestion to…” and “I didn’t even think about the lens I was using to write this–I appreciate the idea to use a different lens for the same story” are common. These responses do not come from the markings of others on a page; they are not a result of flat comments made in red ink in the margins. And neither do they come from just one person. Instead, they are the result of several pairs of eyes on the same paper, talking about the writing and not the writer. They are the result of the writer asking for and listening to verbal input on their writing. As the group members talk about the writing, their ideas and suggestions evolve in a way that could not have happened had they just read the writing and written responses and suggestions to it. They had to talk about it. They had to respond to what others said about it. They had to have genuine, focused conversations.

The partner and small group work we do during SI also lends itself to genuine conversations. Some conversations help us create meaning. I overheard someone say, with surprise in her voice, “It took all three of us to figure out how to say that!” While working through a close-reading of informational text with a partner, one pair talked about the definition of a word, and mulled over whether understanding its meaning affected their task. They wondered aloud if they had the ‘right’ meaning, and who they could ask for verification. Other conversations help us understand a process. I heard, “I think this is what we’re supposed to do…” followed by, “Oh, I get it. Now it makes sense. First we do…and then…. Thanks!” As we participated in these conversations, I was reminded again and again of the necessity of transferring this into practice in my classroom. True, what these conversations look like needs to be carefully scaffolded. I need to model my thought process through a think-aloud using my writing as a mentor text. I need to have students help me ‘act out’ what a writing group looks like. I need to visit groups as they try it out, offering feedback and praise. True, with these habits as a core in my classroom I will have a room where a visitor walking by might think my students lack discipline. But more importantly, it is also true that were visitors to stop in and listen for a while, they would be drawn in by the learning they see taking place. I want to hear that talk. I want that learning to take place.

Change doesn’t come without time, work, and perhaps some resistance. But the more I think about the place of conversation in the classroom, the more I talk with others about it, the more certain I am that it is an essential part of any learning environment. I look forward to hearing what my students have to say!

Kathy Kurtze teaches English and Drama at Carson City-Crystal High School in Carson City, Michigan, and is an active teacher consultant as a co-director of the Chippewa River Writing Project at CMU.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.