In celebration of their union, “Close Reading” and “Critical Reading” will now be addressed as simply “Critical Reading.” Please update your planbook accordingly.

In my first post of this series, I discussed and defined a problem that I see: that my colleagues and I are all using the term “Close Reading,” but we all have a different interpretation of what this means, and what it looks like in our classrooms. What is it that we are actually doing when we say we are doing “Close Reading”—and is it enough? In my second post, I read articles advocating for “Close Reading” and articles criticising it. As I read, I realized quickly that even the experts don’t agree on what “Close Reading” is and what it should look like in the K-12 classroom. In some cases (I’m looking at you, David Coleman), the experts seemed to disagree with even themselves.

Of course, the true issue is not what we call what we are teaching students to do when they are reading; the real issue is what we are teaching students to do when they are reading in our classrooms and in the world.

I truly believe that we must teach students to read closely for evidence, as well as to read critically, for inferences and ideologies—it is as important to read between the lines and to read for what is not being said as it is to read the words on the page. I believe that context and reader response are as important as the artistry of the words (and the claims and supporting evidence). I believe that “Close Reading” is simply not enough—and that “Critical Reading” cannot occur if students are not reading closely. We cannot simply “do Close Reading” if we want to truly teach our students how to read their world.

I truly believe that we must teach students to read closely for evidence, as well as to read critically, for inferences and ideologies—it is as important to read between the lines and to read for what is not being said as it is to read the words on the page. I believe that context and reader response are as important as the artistry of the words (and the claims and supporting evidence). I believe that “Close Reading” is simply not enough—and that “Critical Reading” cannot occur if students are not reading closely. We cannot simply “do Close Reading” if we want to truly teach our students how to read their world.

So, for the sake of clarity and consistency, I will change the language that I use in the classroom and change the title of the graphic organizer that I use. I will add a section to the graphic organizer that asks students to discuss and analyze the ideology of the writing. In our daily conversations in class, I will use the terminology, “Critical Reading,” from now on and explain to my students, colleagues, and administration that “Critical Reading” includes “Close Reading.” I will take the stand that these are not separate skillsets and they can’t be taught in isolation. “Close Reading” alone is not enough.

Maybe this misunderstanding is why so many of us have been confused. We’ve been trying to identify and define separate skills, and teach and assess them formatively and summatively as separate items. But skilled readers do all of these things—analyze word choice and sentence structure, ask questions of the text, make inferences, push back against the argument, verify evidence, make connections both historically and in our present society—all of the time with every text they approach. We don’t use one skill on Monday and another on Wednesday. We need to communicate with our students and with our colleagues that skilled critical reading encompasses and synthesizes all of these individual analytical pieces.

In my classroom, “Critical Reading” will:

- look at the diction and syntax, and determine what rhetorical choices the author is making and how these choices impact the reader

- discuss the not only factual details, but also the power of the imagery the author creates

- identify and analyze the tone of the piece and determine both the attitude that the author holds and the mood that is being conveyed

- discuss the claims, assertions, and contentions the author makes, the supporting evidence that the author uses, and the argument the author is making

- look for the inferences, consider what is not being said, and who is not being addressed

- unpack the stance and the ideology, and reflect on the emotional, social, and political impact of the message.

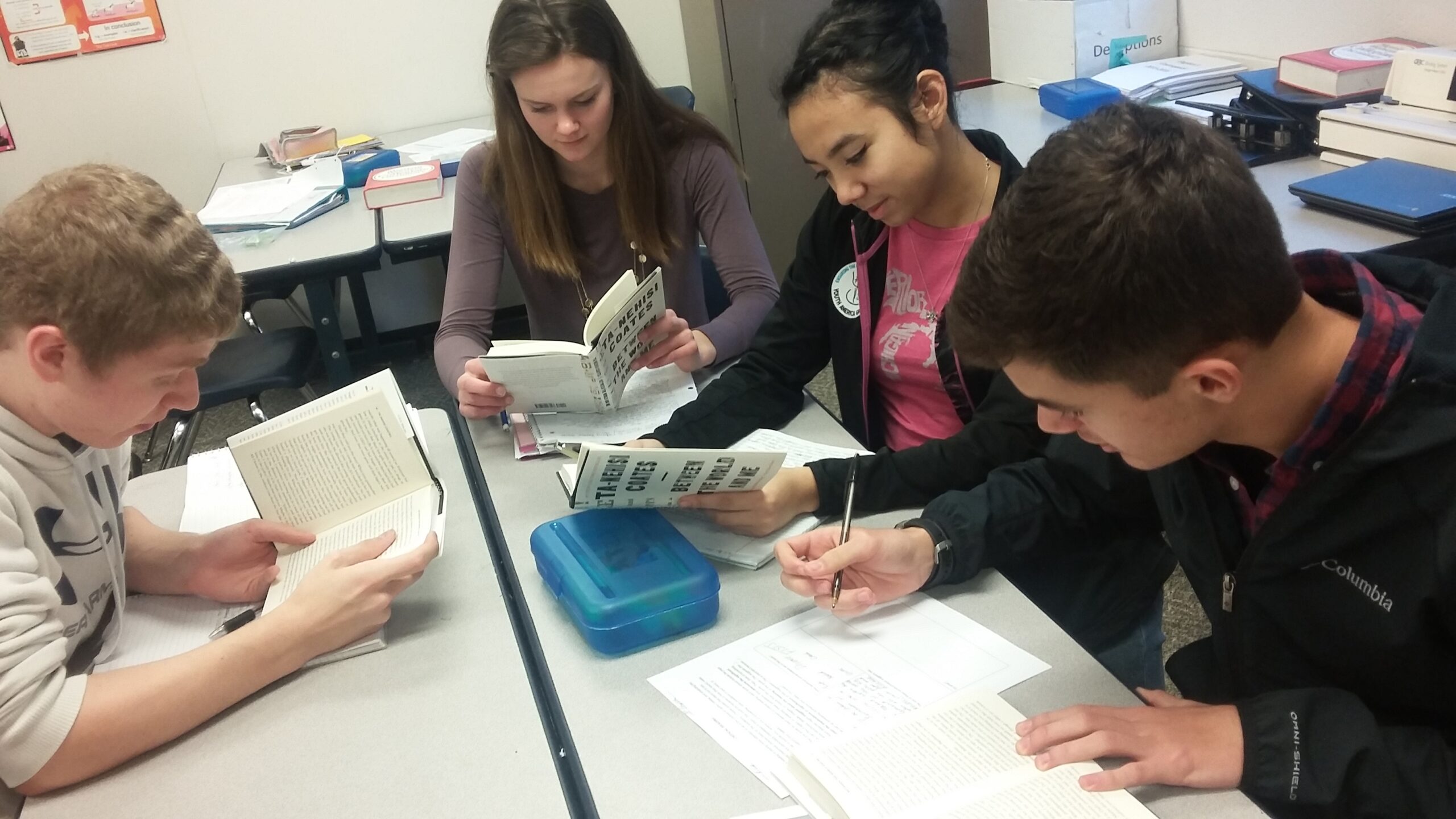

I truly believe that my students will engage at a higher level with the texts they encounter in their daily lives if they have practiced all of the aspects of “Critical Reading” throughout the year in my classroom. My hope is that they continue to read with a critical eye long after they leave my room. So far this year, I am seeing a deeper level of engagement from them as they critically read not only the traditional literature in the ELA classroom, but also the websites they are using for their independent research projects, the SAT prompts they are writing to, and their own writing and the writing of their peers as they work in peer groups. The reading they are doing is both close (understanding the diction and imagery) as well as critical (understanding the political implications of this word choice).

I truly believe that my students will engage at a higher level with the texts they encounter in their daily lives if they have practiced all of the aspects of “Critical Reading” throughout the year in my classroom. My hope is that they continue to read with a critical eye long after they leave my room. So far this year, I am seeing a deeper level of engagement from them as they critically read not only the traditional literature in the ELA classroom, but also the websites they are using for their independent research projects, the SAT prompts they are writing to, and their own writing and the writing of their peers as they work in peer groups. The reading they are doing is both close (understanding the diction and imagery) as well as critical (understanding the political implications of this word choice).

As an example—once my students spend time discussing the word choice of John Steinbeck in The Grapes of Wrath and unpack why he would have chosen the word “monster” to describe the economic and political machine acting on the tenant farmers in Chapter 5, they will better grasp the undercurrents of tension and the incredible power of language not only in Steinbeck’s context but also in our current political debates. Once students grapple with the controversial final scene of the book and discuss the ideology that runs throughout the text, they will recognize the call to action that Steinbeck presents—not just in the context of the dust bowl, but in today’s society as well.

It’s simply not enough to determine meaning from, as Coleman has argued, “what lies within the four corners of the text.” Our students today need to understand the context; they need to grasp the ideology; they need to analyze the implications of what is said and what is not said; they need to understand the power of the stylistic choices the author has made. It’s only through “Critical Reading” that students will hear the messages that these authors are sending. The literature we read is not meant to simply stand alone as art to be appreciated and closely read; it is meant to inspire us to think critically and spur us to action for the greater good.

So, in this blog series, I have not only named the elephant — the varied definitions of close reading — but also identified what it needs to look like in my classroom. It’s up to me to challenge my students to read both closely and critically. Only then will they begin to respond personally, not passively, and truly engage not just with the literature in my class but also with the many modes of texts they encounter in their daily lives.

Sharon Murchie is a high school ELA teacher in Bath, MI. She is a teacher consultant for Red Cedar Writing Project (2005) and Chippewa River Writing Project (2015). She blogs personally at mandatoryamusings.blogspot.com, and she is working on her first book.

Sharon Murchie is a high school ELA teacher in Bath, MI. She is a teacher consultant for Red Cedar Writing Project (2005) and Chippewa River Writing Project (2015). She blogs personally at mandatoryamusings.blogspot.com, and she is working on her first book.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.