Connecting Positive YA Memories to Reading Unbound, The Book Whisperer, and Our Students

This post is the first in a series designed to connect teachers’ remembered childhood and/or YA independent reading experiences and their current teaching practices to Jeff Wilhelm, Mike Smith, and Sharon Fransen’s new book, Reading Unbound: Why Kids Need to Read What They Want and Why We Should Let them. Although this first post is single authored by Elizabeth Brockman, future posts will be co-authored by leadership team members and teacher-consultants from both the Chippewa River and Saginaw Bay Writing Projects.

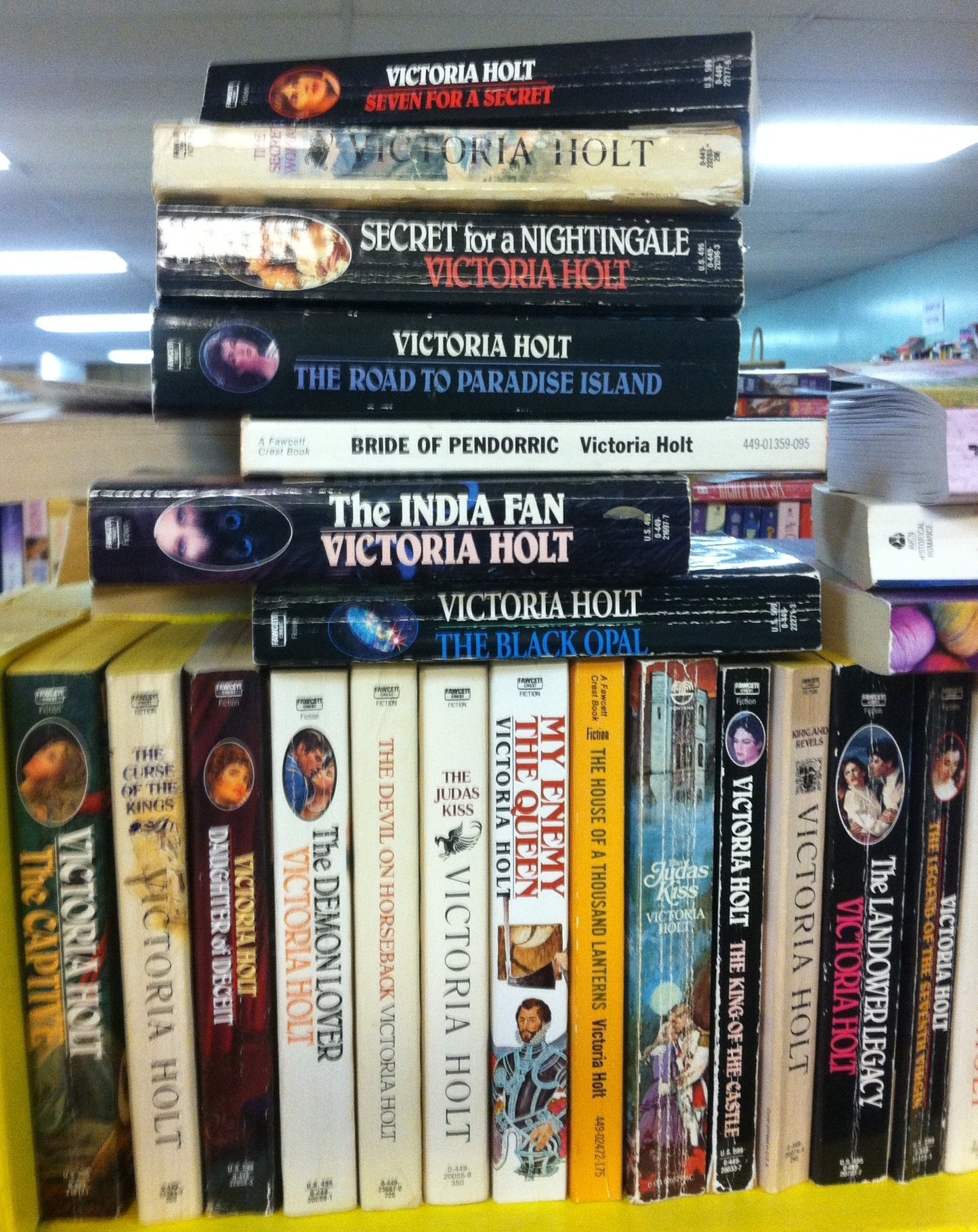

I have no childhood memory of my parents reading for pleasure. My father was an American history professor who read for work every evening, but never fiction, and my mother was a former elementary teacher who read aloud to her brownie troops year after year, but that was about it. No, I didn’t learn to read for pleasure from my parents; I learned from my older sister, Susan, whom I idolized. Whatever Susan did, I did too, and I remember when she was devouring romance novels by an author named Victoria Holt. Menfreya in the Morning. On the Night of the Seventh Moon. The Shivering Sands. Naturally, I followed suit.

It’s surely an oversimplification, but most Victoria Holt books of my early teen years seemed to follow the same basic plot. A smart, single, and “mature” heroine—usually 23 or 24—living in a previous century finds herself in reduced, or at least different, circumstances prompting her to move to a new land among new people. There, in a dark and foreboding ancestral home by a large body of water, she meets two men: one fair haired and of good character and the other dark haired and of suspicious character. As the narrative propels the heroine through a sequence of serious and eventually life-threatening conflicts, the reader is led to believe the heroine will marry the fair-haired man. In a pivotal plot twist near the end of the book, however, the men’s true characters are revealed, and they are the opposite of what they originally appeared; and then the heroine marries the dark-haired man whom she has truly loved all along anyway.

Last summer, I found a new Victoria Holt book, and I’ll be darned if the text didn’t introduce me to a French woman in her mid-twenties forced to move from La Province during the French Revolution to the UK, where she is romantically pursued by her two stepbrothers: a dark-haired one of questionable character and a fair-haired one who is steady and staid. From the first page, I claimed affiliation in the Victoria Holt Fan Club and slyly looked for clues to reveal the men’s true characters that I was confident other, less attentive readers might miss. Though admirable qualities in the dark-haired stepbrother soon emerged, the fair-haired brother had me stumped. From every angle, he seemed to be an all-around decent guy–not unlike Ned Nickerson in Nancy Drew or Laurie What’s-His-Name in Little Women. Then halfway through the narrative progression, the heroine marries the fair-haired brother but later, in a weak moment, begins an affair with the dark brother. After several trysts, the heroine is wracked with regret, especially after learning she’s pregnant but doesn’t know which brother is the father. I’m thinking … hair color, darling … but I digress. I kept wondering how Victoria would resolve this love triangle, and then she takes the easy way out. The potentially life-threatening conflict that heroines from my early teens encounter eventually comes into play, and the dark-haired brother is killed, leaving said heroine to live out her days faithfully—but only sort of, given her momentary lapse in judgment. End of Story.

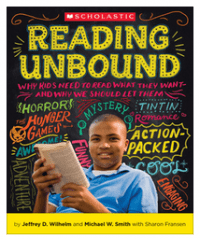

Anyone reading this post would agree that I took pleasure in returning last summer to a favorite childhood author, but I must have taken even greater pleasure in reading Victoria Holt back in the 70s because I have read, at latest count, over thirty of her romance novels. My YA reading experiences bring to mind Jeff Wilhelm, Mike Smith, and Sharon Fransen’s fabulous new book, Reading UnBound: Why Kids Need to Read What They Want and Why We Should Let them, which reports results of a qualitative study of voracious high school readers. On the most fundamental level, the study celebrates and legitimizes the power and importance of teenagers’ independent reading by demonstrating that if kids don’t take pleasure in reading, they won’t ever become readers in the first place. The study also demonstrates that reading pleasure is a more complicated phenomenon than we may have realized. In fact, the study suggests that voracious readers derive not just one, but four different kinds of reading pleasure: social pleasure, play pleasure, work pleasure, and intellectual pleasure. The study also provides results regarding the intensity, duration, and timing of reading pleasures, as well as chapters devoted to currently favorite teen genres.

Thanks to Reading Unbound, I’m initially forced to rethink the limitations associated with childhood memories of my parents’ reading habits. Though my father’s nightly professional reading and my mother’s brownie troop read alouds may not have prompted play pleasure, they surely fostered work, intellectual, and even social pleasure, as Wilhelm, Smith, and Fransen define them. Also, why did I associate “reading for pleasure” solely with fiction? An expanded definition would honor, for example, my mother’s daily reading of cookbooks and recipes swaps, as well as my father’s perusals of gardening and birding books. And, finally, what do I make of my own early teen experiences reading over thirty Victoria Holt romance novels? How do my memories of reading for pleasure stack up with the reading experiences of the teen subjects showcased in Reading Unbound? Further, what’s the connection to my early years of teaching middle and high school English, as well as my current teaching roles at CMU, especially the CRWP?

In future blog posts, I hope to try to answer these questions and others like them, but the discussion will be enriched by the voices of other NWP teacher-consultants—both from the Chippewa River Writing Project and the Saginaw Bay Writing Project—who will read closely Reading Unbound and will publish co-authored or at least multi-voiced blog posts about our respective childhood and/or YA reading experiences and, equally important, how these remembered reading experiences impact and/or intersect with our roles as teachers and as writers. The timing of this blog series is especially good as the CRWP and SBWP prepare to welcome Donalyn Miller, highly acclaimed independent-reading advocate and author of The Book Whisperer and Reading in the Wild as our 2015 MLK Day Writing Conference keynote speaker.

Stay Tuned.

Elizabeth Brockman is a founding co-director of the Chippewa River Writing Project. A former middle and high school English teacher, Elizabeth is currently a professor in the English Department at CMU, where she teaches composition and composition methods courses.

Elizabeth Brockman is a founding co-director of the Chippewa River Writing Project. A former middle and high school English teacher, Elizabeth is currently a professor in the English Department at CMU, where she teaches composition and composition methods courses.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.