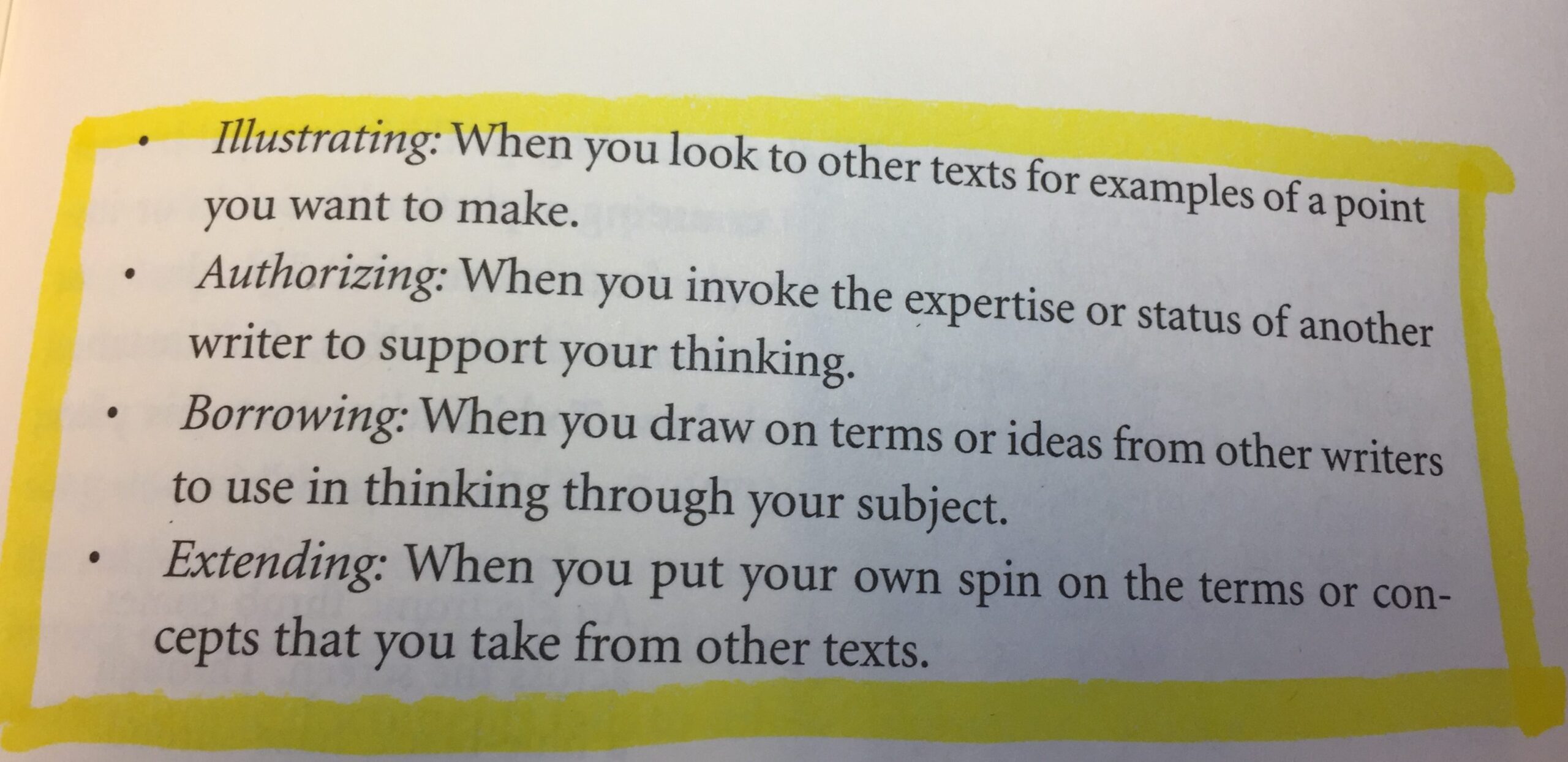

The nuanced claim, authorizing, illustrating, and borrowing: These are some of the moves used in argument writing as promoted by Joseph Harris in Rewriting: How to Do Things with Texts, a foundational text of The College, Career, and Community Writers Program (C3WP), sponsored by the National Writing Project (NWP). After teaching and reinforcing these moves with my sophomores and juniors during the fall 2016 semester, it was a simple step to prepare them for the SAT essay, because all of these moves are easily applicable.

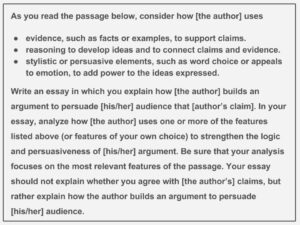

The SAT on-demand essay, as anyone who has prepped students for taking it knows, is a 50-minute written rhetorical analysis of a non-fiction article. This rhetorical analysis is the final test in the SAT exam – when students are already drained and hungry. Last year, when I prepped my students, I focused on Aristotle’s appeals of persuasion – logos, ethos, and pathos – to look for in the article they were to analyze. This year, I improved the SAT practice opportunities by combining Aristotle’s appeals with the Harris moves from the C3WP, and the outcome, I believe, will be a better SAT essay from the students.

I first instructed students to take the time to analyze and then annotate the article on which they were practicing their analysis skills. They were used to taking these initial steps because we had practiced these moves every time we began another C3WP mini-unit and because each one begins with the careful reading and analysis of a text set comprised of three nonfiction articles. The box at the end of the SAT test article to be analyzed has the author’s claim, so students were instructed to look at that box first so that they knew what the article was about. “Think: How does the article title support the author’s claim?” I asked them. This move helped the students focus on what the author was going to say. Hopefully, it also helped steady students’ already frayed nerves. Then I told them to look at the bolded author blurb, found just below the article title. This is the ethos of the author, his or her credibility or expertise in the topic at hand. This year, I was able to ask, “How does the author’s ethos connect to what we’ve learned about argument writing?” My students almost immediately responded, “The author’s ethos is Authorizing – and, we don’t have to hunt for it in the article because it’s right in the bolded blurb below the article title!” My students were relieved because they had been practicing this move all year, so the Authorizing in their analysis essay was easy.

As the clock ticked away the 50 minutes of practice, most of my students took the time to analyze and annotate in the margins. They looked for the sentence containing the author’s claim so they could quote it in their analysis. (“Don’t quote from the box at the end of the article,” I told them, “because that is not what the author specifically said.”) They marked the text for claim-supporting evidence or logos, and word choice depicting pathos. They also looked for Illustrating – those author-used examples that they could reference in their written analysis. My more skillful writers also looked for the special descriptive phrases that they could Borrow.

When they had finished annotating, almost every student jumped into the actual writing. I had explained that taking the time to make a short outline, to plan their writing, helped with their organization of their writing. However, as they explained to me, they already knew what should go into the short introduction, the body, and the conclusion if they got to it, because they had written so many essays while practicing the C3WP moves, so taking the time to outline their essay was superfluous. I had also suggested that they take a minute or two to decide whether or not they thought the article they were analyzing was well written. Their comment: “SAT had better not give us a poorly written article to analyze. That wouldn’t be fair!” I had to agree, although I pointed out that a few of the SAT practice essays had, in fact, not been particularly well written. However, my students were unpersuaded.

The chart below compares the language used in the Harris argument-writing text, the literary terms as developed by Aristotle, and the terms for the SAT Essay Analysis.

[table id=1 /]

My classes wrote 3 practice SAT essays. Their analyses improved with each practice, although the majority of the class did not finish their written analyses within the 50 minute time frame. My students’ actual content and structure improved significantly. As they used the Harris moves of Authorizing, Illustrating and Borrowing in their writing, they began to write with confidence and implement the authority of their own voice. I credit their use of the College, Career, and Community Writers Program moves as instrumental in their improvement.

References:

Harris, J. (2006). Rewriting: How to do things with texts. Utah State University Press.

SAT Essay. (2017, January 31). Retrieved from https://collegereadiness

Deborah Meister is a high school language arts teacher at Fellowship Baptist Academy in Carson City, MI, and a Teacher Consultant at the Chippewa River Writing Project. She has co-directed the CRWP Middle School Writing and Technology Camp for the past three summers at Central Michigan University with author Jeremy Hyler.

Deborah Meister is a high school language arts teacher at Fellowship Baptist Academy in Carson City, MI, and a Teacher Consultant at the Chippewa River Writing Project. She has co-directed the CRWP Middle School Writing and Technology Camp for the past three summers at Central Michigan University with author Jeremy Hyler.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Deborah Meister

Deborah Meister is a high school language arts teacher at Fellowship Baptist Academy in Carson City, MI, and a Teacher Consultant at the Chippewa River Writing Project. She co-directed the CRWP Middle School Writing and Technology Camp for three summers at Central Michigan University with author Jeremy Hyler. She has presented on various writing topics with Dr. Liz Brockman, Kathy Kurtze and Janet Neyer at the NWP Midwest Conference, and the National Council of Teachers of English Conference. Her work has also been published in the Language Arts Journal of Michigan.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.