This post is the second in a series designed to connect teachers’ remembered childhood and/or YA independent reading experiences and their current teaching practices to Jeff Wilhelm, Mike Smith, and Sharon Fransen’s new book, Reading Unbound: Why Kids Need to Read What They Want and Why We Should Let Them.

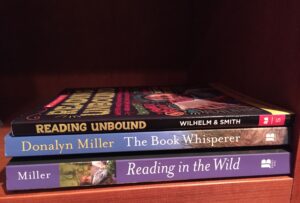

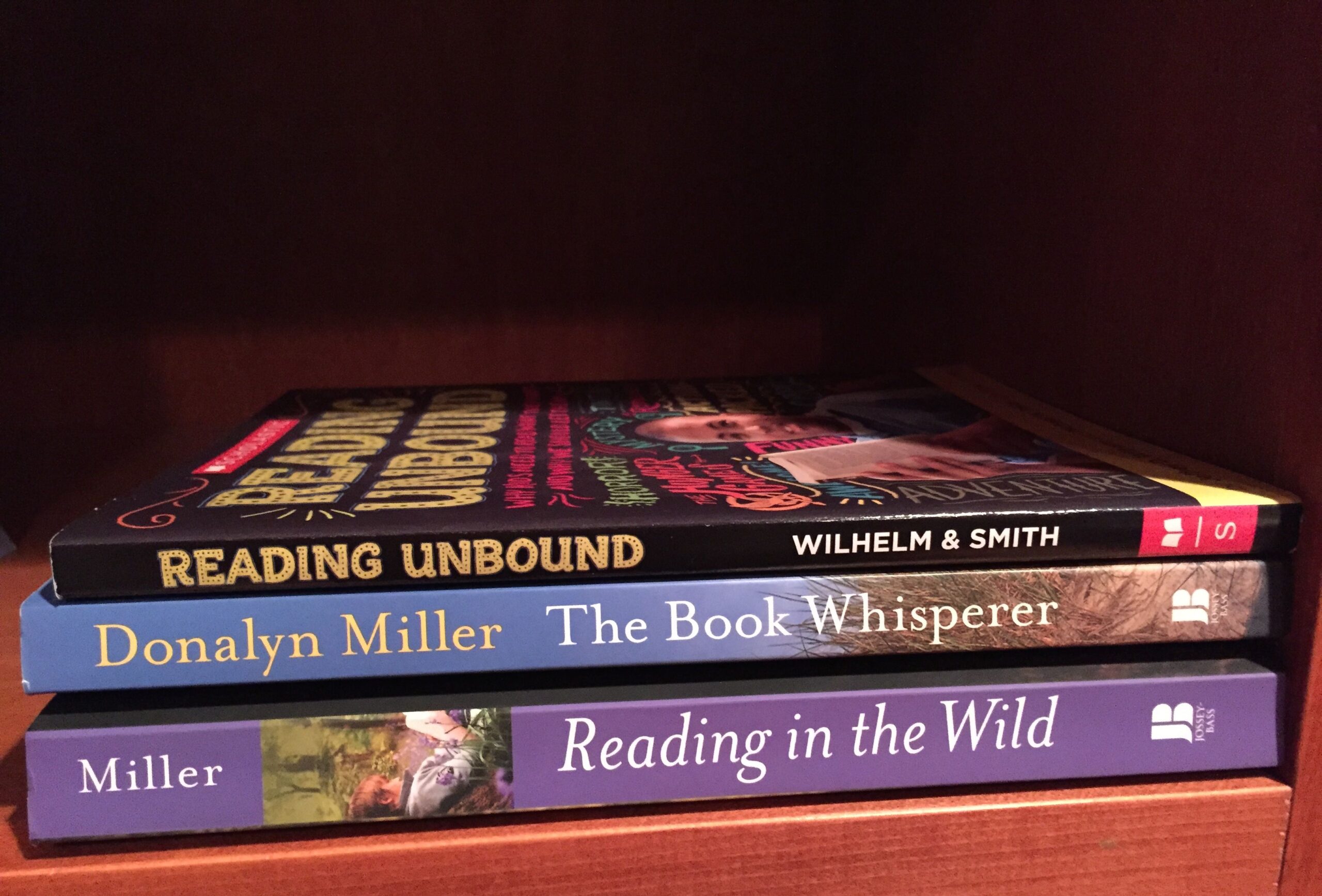

As a CMU English professor, I have for years observed firsthand Silent Sustained Reading (SSR) in my students’ field experiences and student teaching placements, and most resemble the SSRs from my own teenage years, the years I was devouring romance novels by Victoria Holt (as I explained in my first blog post). During both these long-past and more recent SSRs, the class sessions tend to run the same way: students read silently during all or part of a class, and the teacher energetically does the same, the better to serve as an adult model for students to emulate. This teaching model, though time honored and well intentioned, is inherently different from the model that Donalyn Miller–our 2015 MLK Day Conference keynote and author of The Book Whisperer and Reading in the Wild–advocates, with reading conferences, book challenges, bursting-at the seams classroom libraries, and more.

As a result, I recently encouraged one of my undergraduates, Maria Kioussis–a pre-service teacher who completed a field experience at Beal City High School in rural Mid-Michigan–to request permission to conduct reading conferences during SSR, and her host teacher readily agreed. In her field experience journal, Maria documented what took place during the student conferences, and I had the opportunity to read and respond. Though the journal is based upon Maria’s memories, as opposed to transcribed tapes, of a single class session and she conferenced with solely two groups of five students, Maria’s comments are intriguing, especially if the purpose of SSR is to foster voracious independent readers–a pedagogical goal identified as crucial beyond measure in The Book Whisperer, Reading in the Wild, and Reading Unbound. And, as Nancie Atwell succinctly reminds us in the third edition of her highly acclaimed In the Middle, “The results of every major assessment of reading ability–NAEP, SAT, PISA, you name it–show that the most proficient student readers are those who are habitual independent readers” (23).

As a result, I recently encouraged one of my undergraduates, Maria Kioussis–a pre-service teacher who completed a field experience at Beal City High School in rural Mid-Michigan–to request permission to conduct reading conferences during SSR, and her host teacher readily agreed. In her field experience journal, Maria documented what took place during the student conferences, and I had the opportunity to read and respond. Though the journal is based upon Maria’s memories, as opposed to transcribed tapes, of a single class session and she conferenced with solely two groups of five students, Maria’s comments are intriguing, especially if the purpose of SSR is to foster voracious independent readers–a pedagogical goal identified as crucial beyond measure in The Book Whisperer, Reading in the Wild, and Reading Unbound. And, as Nancie Atwell succinctly reminds us in the third edition of her highly acclaimed In the Middle, “The results of every major assessment of reading ability–NAEP, SAT, PISA, you name it–show that the most proficient student readers are those who are habitual independent readers” (23).

In her field experience journal, Maria initially writes:

[Among the ten students,] I found a mix of self-identified readers, non-readers, and re-discovered readers. One student shared that the book he was reading now was the first book he has read in three years, but he actually likes it … With the exception of maybe 1 or 2 students, all of the students I conferenced with were reading, although not … all of the students were excited about what they were reading. I got a lot of responses that went like this: “Well, up until where I am, X, Y, and Z happened, but it’s kind of boring so it’s taking me a while to get through it.”

Maria’s comments about a “re-discovered reader” are heartwarming. After all, what teacher wouldn’t be thrilled that a student was reading and enjoying a book for the first time in three years, thanks to SSR? However, the goal of fostering voracious independent reading among all students is not likely to be achieved if, as Maria suggests, 10% – 20% of her students aren’t reading outside of SSR time and a significant number of students don’t seem to be taking pleasure in their books.

Maria continues:

[Student disinterest] sounded like a problem picking the right book, so I began asking students how they chose their books or where they found them. Many students chose from the classroom library or based [their choice] on a parent or grandparent’s suggestion. Multiple boys told about their grandfather’s war books and one girl told me her mom gave her a “stack of books with the word, heaven, in the title.” While some of these suggested titles are good books and some do align with the interests of the students, many lacked an adolescent protagonist that the students could relate to.

On the other hand, the excited students almost all were reading YAL [young adult literature].

Maria’s observations align with current thinking regarding the crucial relationship between reading for pleasure, voracious independent reading, and effective book selection. While family libraries may be a viable source of good books, Maria reasonably points out that YA books are more likely to inspire pleasure among teenage readers. Her observations bring to mind Part II of Reading Unbound, which showcases currently popular YA genres: romance, dystopian fiction, horror stories, vampire/immortality novels, and Harry Potter/fantasy. According to Miller (among others), teachers need to make these kinds of high interest books accessible to students by curating extensive classroom libraries, and they need to provide teacherly guidance in helping students select books and document progress.

As previously indicated, Maria’s field notes are … just notes, and one set of notes at that. They certainly don’t have the heft to make or support broad-based claims about adolescent reading, in general, or even about adolescent reading, in particular, at BCHS. On the other hand, Maria’s field notes reflect reading conferences inspired by the same good impulse that prompted Wilhelm, Smith, and Fransen to write Reading Unbound: “Why not ask young people directly (my emphasis) what they get from their reading of such texts? Why not ask them how they experience and use them? And so we did” (9). Wilhelm, Smith, and Fransen, of course, are different from most middle and high school English teachers who don’t have the time or resources to conduct large-scale, original research projects regarding students’ independent reading practices. Most teachers I know are stretched beyond the breaking point, barely able to juggle professional goals, extracurricular responsibilities, and personal obligations.

Nevertheless, these same teachers could certainly put down their own independent reading books during SSR, like Maria, to directly ask students what they are reading, if they are or are not taking pleasure in doing so, and–most importantly–why. According to Wilhelm, Smith, and Fransen, taking pleasure in reading (play pleasure, work pleasure, social pleasure, or intellectual pleasure) is the only path to becoming a voracious independent reader, so students’ answers and reflections are clearly worth teachers’ undivided time and attention. Further, Wilhelm, Smith, and Fransen insist that “home and school should be places where readers are nurtured, supported, and assisted to create their own active reading lives, connected to their own life journeys. This is the only way in which students will become lifelong readers (11). Taking a cue from composition studies, then, we might say that gifting time alone for independent reading is necessary, but insufficient, to foster voracious reading, just as gifting time alone during writing workshop will not automatically foster writing competence.

To “Teachers as Writers Blog” readers who already know that time alone during SSR isn’t enough to foster voracious reading, I offer two words plus seven: Great Job! Please spread the word among your colleagues! For those who still believe that modeling good reading habits is the sole role to play during SSR, I hope you’ll consider reading Reading Unbound and/or attending the 2015 MLK Day Writing Conference at CMU to hear Donalyn Miller speak. She’ll give the keynote address and lead two conference sessions (Register Here). And teachers with little or no professional development time or funds will find a great resource in Tim Pruzinsky’s “Read Books. Every Day. Mostly for Pleasure,” which appeared in the March 2014 issue of English Journal.

In 2015, how might you re-imagine your role in SSR… ?

Elizabeth Brockman is a founding co-director of the Chippewa River Writing Project. A former middle and high school English teacher, Elizabeth is currently a professor in the English Department at CMU, where she teaches composition and composition methods courses.

Elizabeth Brockman is a founding co-director of the Chippewa River Writing Project. A former middle and high school English teacher, Elizabeth is currently a professor in the English Department at CMU, where she teaches composition and composition methods courses.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.