I teach in an inner-city school and work with students who have a variety of disabilities including specific learning disabilities, autism, behavior disorders, and many other labels. My students are smart and capable, but they’re not always able to display these traits without some accommodations. Two years ago, I was assigned a caseload of 13 amazing, funny, and energetic students. I had worked with many of the students for at least one school year and very much looked forward to working with all of them again.

The hitch was that I was assigned to teach English Language Arts to this group of 11 14-year-olds spanning three grade levels and testing between kindergarten and fourth-grade reading levels in a 60 minute period, without being provided a curriculum source we could share. Many of the things I liked most about these students (their big personalities, decisive natures, and an unending supply of energy and enthusiasm) also made them very demanding members of a class.

I had spent the previous time we had worked together in much smaller groups spanning two or fewer grade levels and usually six or fewer students. I had tried before to work in centers doing short mini-lessons and sending students off to work independently, but it just didn’t work well for students who wanted and needed my full attention. In my previous writing assignments, I spent a lot of time consulting with students one-on-one, conferencing frequently, and helping them edit and revise every sentence until they produced a draft that satisfied them and me. There was no way I would have time for this kind of one-on-one attention in my writing assignments this year. Besides, many of my biggest personalities in the group would often capitalize quickly on my divided attention to joke around or otherwise stall to keep from working. This kind of behavior was especially frequent on my most difficult assignments, suggesting that students were likely to misbehave when they didn’t feel confident enough to complete an assignment on their own.

I agonized over what to do and how to address the fact that I had a class that would require a firm hand and a sense of accountability and watchfulness from me while I also had a style that meant engaging deeply with an individual student, writing in a one-on-one setting as frequently as possible. I decided that the answers to my problems could be found by going back to one of my old favorites: They Say, I Say: The Moves That Matter in Academic Writing by Gerald Graff and Cathy Birkenstein. This was a short book that broke down strategies authors often employ for academic purposes and even provided templates for the reader to use in his or her own writing.

I’d read the book as a graduate student and taught the book as both a graduate teaching assistant and adjunct faculty member. I love They Say, I Say and have relied on it greatly myself as both teacher and writer. Each perusal reminded me of another “move” I hadn’t used in a while and refreshed my writerly “bag of tricks.” I was purposeful in pairing chapters of the book with essays I had assigned to my college freshmen and sophomores and encouraged them to make use of the templates as much as they saw fit to great effect.

I decided with some hesitance that the best way I could “get through” this year would be to make greater use of templates and to provide my current students with templates that went so far as to provide a sentence starter template for almost each sentence of the essay. I worried this dependency on templates would stifle their creativity and make the essay writing process far too easy for them, but I also thought it might make it possible for me to maintain a high level of control over the class by ensuring everyone would at least be able to keep working on something. I told myself that if embracing They Say, I Say had worked for college students, there was no reason to believe it might not also work for middle school students.

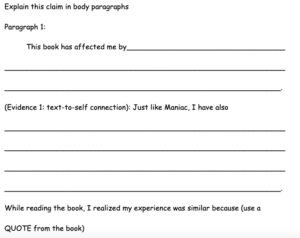

Rather than reading chapters of They Say, I Say with my class and encouraging the use of the templates provided within each chapter, I wrote my template based on my rubrics and assignment prompts to provide students with the foundation for a strong essay. I left plenty of room for student writing within the template, hopeful that they would complete the sentences in detail. I introduced the assignment and they watched as I wrote my mentor text, thinking aloud as I explained my own claims and chose examples from the text or texts we were using as I filled in the templates.

I then sent students off to start their own drafts and began individually conferencing with them as they drafted. What I found was that my students’ work was much better than I had expected it to be, especially in early drafts. Yes, many of their sentences began in the same way; yes, it was obvious to a reader grading them in one sitting; however, when read individually, the essays displayed some truly mature and unique ideas in response to the topic provided. I’d not only achieved my goal of maintaining control over students and leveling the work to meet their various levels of functioning, but also had helped them produce completed essays that showcased their best thinking.

As we moved through the year, many of my students produced essays that were indistinguishable from some of the essays their general education peers were producing. Freeing them up to make choices about the ideas in their essays, rather than the word choices, had put on display exactly what I knew about them from the start: they were smart and capable! Students also began to show more pride in their work and took more ownership over their assignments than ever before. They asked me to print extra copies so they could show other teachers and their families. I often “publish” some of their shorter writing assignments throughout the year by displaying them outside of our door. This habit had filled me with pride and them with ambivalence, but suddenly, I had to reassure them that yes, these essays would be on display.

As time wore on, students became less reliant on the templates and started asking me during conferences whether they “had” to use my sentence starters or found places where they wanted extra sentences or to go in other directions. While not all of these ideas always met assignment guidelines, I had never gotten middle school students to come to me and ask if they could write more anywhere at all about anything I’d ever assigned. I had to ask myself “how did that happen?” See my next post for a reflection on why this worked!

To view samples of the templates and rubrics Megan created, click here.

Megan Kowalski is a Chicago Public Schools teacher and a 2009 participant in the CRWP Summer Institute. She teaches 6th-8th grade reading and math to students with disabilities, where she enjoys sharing her passion for reading and writing with middle school students.

Megan Kowalski is a Chicago Public Schools teacher and a 2009 participant in the CRWP Summer Institute. She teaches 6th-8th grade reading and math to students with disabilities, where she enjoys sharing her passion for reading and writing with middle school students.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Megan Kowalski

Megan Kowalski is a Chicago Public Schools teacher and a 2009 participant in the CRWP Summer Institute. She teaches 6th-8th grade reading and math to students with disabilities, where she enjoys sharing her passion for reading and writing with middle school students.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.